Spotting the red flags – in patients and in ourselves

Haemophilia Nurses Association Annual General Meeting, Birmingham March 29th/30th 2019

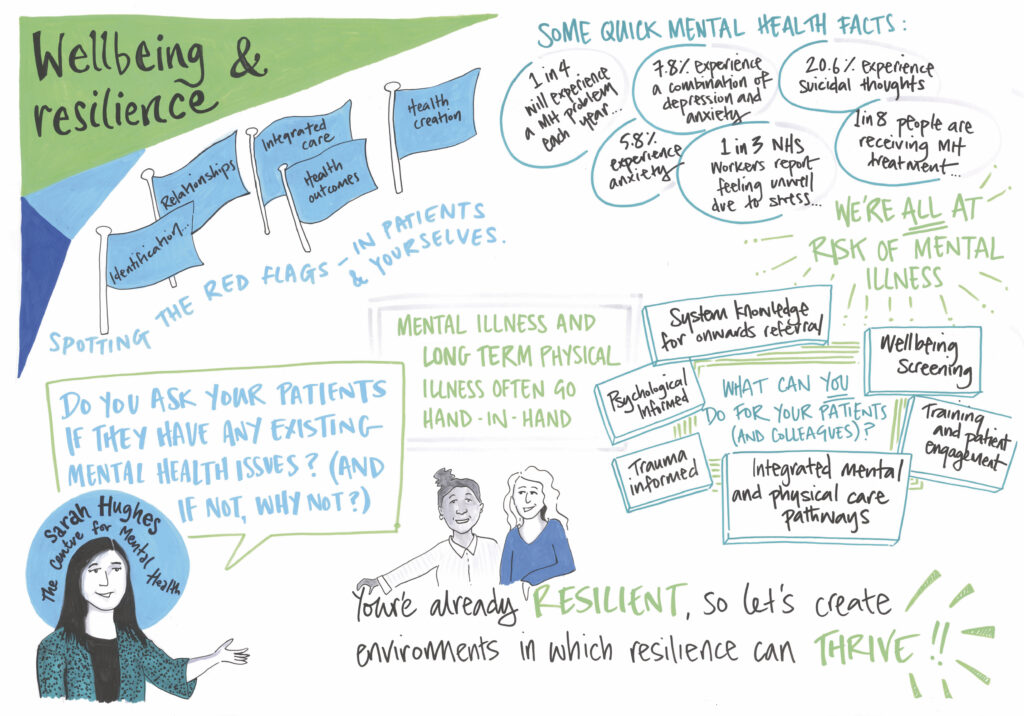

The Centre for Mental Health (CMH) is a charity that aims to do the thinking on behalf of the mental health system through research, economic analysis and influencing policy. Chief Executive Sarah Hughes described its activities as tackling ‘areas other people don’t enjoy looking at’.

Poor mental health is common – everyone has experienced mental distress and about one-quarter of us has a treatable mental illness, the most common being anxiety with depression (8%) and anxiety (6%). Half of people who have a mental health disorder had symptoms by the age of 15.

Everyone is at risk but some factors make poor mental health more likely. Poor mental health and long term conditions go hand in hand, and poor mental health increases the costs of care and is associated with worse outcomes. Tackling this means recognising the red flags but also looking at the relationships health professionals have with one another and with their patients.

Red flags for poor mental health

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Poor housing

- Poverty

- Long term conditions

- Life events

- People from marginalised groups

- Political instability (38% feeling worried, 17% stressed)

The 2017 Stevenson/Farmer review Thriving at Work described a future with greater awareness of mental health issues and a role for everyone in supporting those affected and which recognises that psychological health underpins physical health. Its recommendations have been accepted by the NHS. CMH has developed the Equally Well UK initiative to support efforts to close the gap in care provision for mental and physical health. Guidance on addressing these issues in a school setting is available at https://www.mentallyhealthyschools.org.uk.

For HNA nurses, this means creating the conditions in which mental health conversations can begin, considering wellbeing, and integrating physical and mental health pathways. There’s no need to be a psychiatrist – just be a caring person and take the time to ask ‘How are you?’

A ‘trauma-informed’ approach is critical. This means being aware of the circumstances that affect a patient’s risk of poor mental health and creating an environment and policies that address them, and support staff in doing so. For people with haemophilia, Ms Hughes suggested that the most important action is to talk to them about mental health and the impact of haemophilia.

The signs associated with poor mental health are the same for nurses and patients alike but, Ms Hughes added, it’s a mistake to assume they are easily recognised.

Signs of poor mental health

- Did not attend

- Performance below expected

- Personality change, withdrawn, unengaged

- Difficulty with treatment adherence

- Anxious behaviours

- High expressed emotion

- Reported negative/traumatic life events

- Evident low self esteem

- Hypervigilance

- Evidence of self harm

- Increased adverse health behaviours

Unfortunately, many of the responses that have developed to respond to these signs are judgemental and punitive – for example, high expressed emotion may be perceived as complaining – and there is a need for greater understanding of the factors that underpin these behaviours. Inappropriate responses include overreacting, formulating negative assumptions about the person, and turning a blind eye. Haemophilia nurses should not think that mental health isn’t their business; they should not wait to have expert training before they act, nor should they stop using their intuition.

Nurses are already resilient health professionals, Ms Hughes concluded. They need to create an environment in which that resilience can thrive – this is something that needs action from everyone in the workplace, not only individuals.

Visual minutes by Woven Ink