Not in the job description: On The Spectrum

The characteristics of ASD can be summarised as social impediment, intense focus/interest, sensitivities, the need for routine and repetition, and communication difficulties. Clare James, Paediatric Haemophilia CNS at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital, said they affect individuals to varying extents and, depending on the severity of each, ASD can be classified into three functional levels:

- requiring support (difficulty initiating social interactions and independence hampered by problems with organisation and planning

- requiring substantial support (social interactions limited to narrow special interests, frequent restricted/repetitive behaviours)

- requiring very substantial report (severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal communication skills, great distress/difficulty changing actions or focus)

Someone with ASD and haemophilia may therefore find it difficult to cooperate with their carer. Repetitive behaviours increase the risk of injury or interfere with the need to rest after a bleed. Communication problems make it difficult to talk about fear and pain. Hypersensitivity can make it difficult to use topical agents and dressings whereas hyposensitivity may be associated with a high pain threshold. The importance of routine means that hospital visits and admissions are stressful and treatment changes are difficult.

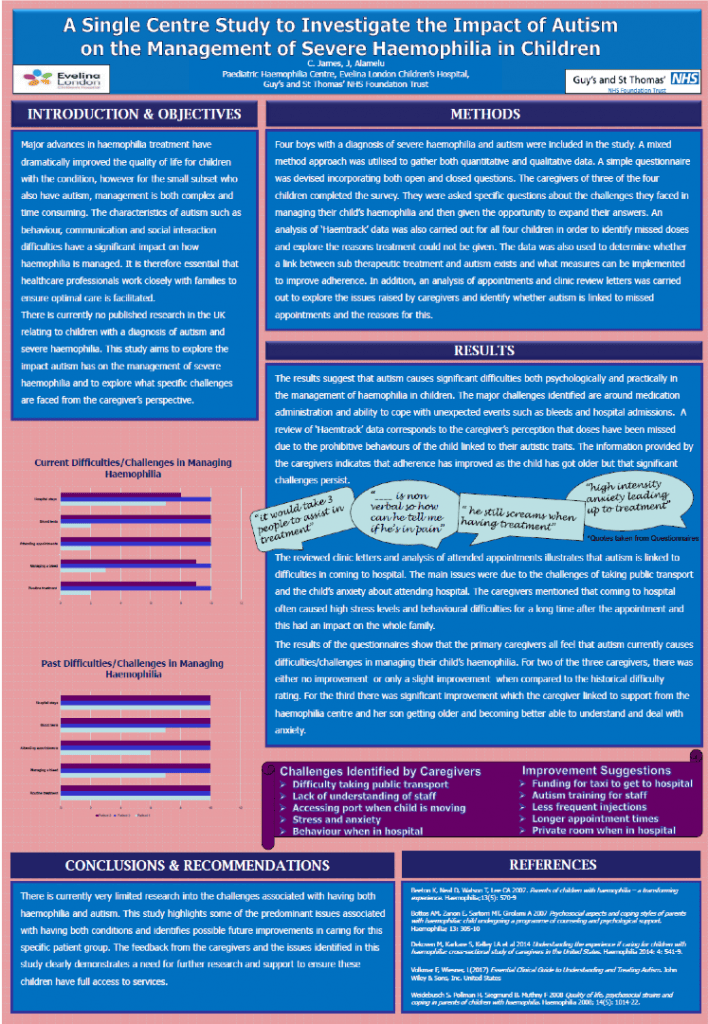

A study by Clare and colleague Jayanthi Alamelu, presented at the 2019 World Federation of Hemophilia Congress in Glasgow, described the perspective of boys with ASD and their parents on haemophilia care. They described severe anxiety and distress associated with administering clotting factor and practical difficulties giving the infusion (one boy requiring restraint). The main challenges of dealing with clinic attendance were associated with difficulties using public transport and sharing waiting areas with people who did not understand the boy’s needs. Visiting the hospital provoked anxiety that would persist long after the visit itself and affect the whole family.

The haemophilia team introduced measures to reduce the burden on the boys and their families. They provided transport to the hospital and a private room to wait in. Staff received additional training about ASD. Treatment was altered to reduce the frequency of injections and longer intervals between appointments were introduced. In practical terms, this meant switching from standard to extended half-life clotting factors for two boys and, for a boy with inhibitors, switching from immune tolerance therapy to emicizumab (which then led to a fear of subcutaneous injections). The boys ranged in age from 7 to 13; help with transition to adult services will be introduced early to ensure ample time to readjust.

Clare concluded with the observation that increasing the proportion of care provided through home visits, and new technologies such as video consultation, could help boys with ASD and haemophilia by avoiding changes to their routine. ASD is relatively uncommon and it would therefore be useful for haemophilia centres to share their experiences.